Structuring Sourcing Projects

Fundamentally, the structure of every sourcing project breaks down into the same two basic parts: who the transaction is between, and how the arrangements are dealt with in the contract.

This sounds simple enough, but of course there are lots of factors which influence what works best. In this series of posts I’ll be looking at the most common structures used, how organisations choose between them and at some of the issues arising from particular types of transaction (such as cross-border international projects).

Common structures

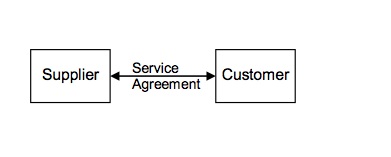

The simplest form of arrangement is where one supplier provides a single service to one customer in one location. In this case the structure is (and can only be) a straightforward contract between the supplier and customer. (I will call this Option 1.)

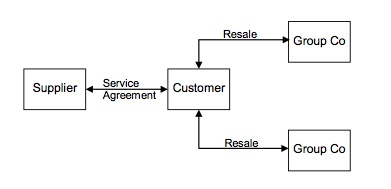

Things become more complicated where group structures have to be allowed for. The three examples which follow illustrate a group of customers each of which wants to benefit from the outsourced supply. This could be a corporate group, or perhaps a consortium of public sector bodies looking to benefit from a joint procurement.

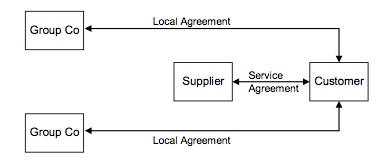

In the first example below (Option 2) there’s a single services contract and the customer then resells or re-supplies the services to other users.

These users could be designated as third-party beneficiaries under the contract but this isn’t essential - the critical link is the one between the supplier and the customer. In particular, it’s vital for the supplier that the customer accepts the role of single point of contact with contractual responsibility for all users. Otherwise the supplier could find itself providing services without any direct way of enforcing payment from either the recipient or the main customer.

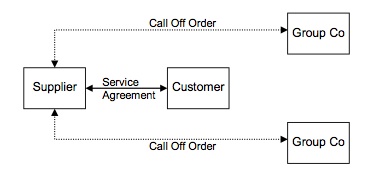

An alternative structure uses a single contract but allows other users to place their own orders with the supplier and then manage the operational relationship direct. The extent to which this ‘management’ is allowed to be truly independent is a matter of taste and can be flexed to accommodate each organisation’s cultural preference. All liability is still channeled through the single contract but the services are supplied in discrete parcels. (This is Option 3.)

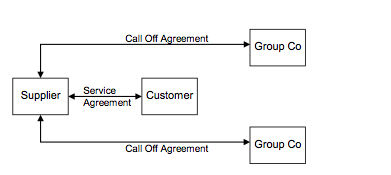

In the next example (Option 4) there is still a central contract but under its umbrella the various users sign their own direct services contracts with the supplier.

There is a choice in this situation about how contractual liability is treated. It can be channeled through the central contract or it can be devolved to each call-off agreement. Where it’s channeled through the main agreement each group company will usually still be liable for paying for its own services, but disputes have to be escalated to (and resolved by) the main customer and supplier.

It’s important also to consider the supplier’s internal group structure and supply chain. In the previous examples we’ve assumed the supplier is entirely responsible for its own sub-contract relationships (not illustrated), but the supplier might prefer to provide services direct from its own subsidiaries, as below (Option 5).

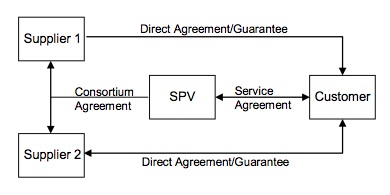

Finally, in some situations there is no obvious candidate for ‘the supplier’. Instead there may be a consortium of suppliers jointly contributing to the overall service and they may decide to set up a special purpose vehicle or ‘SPV’ company through which they will contract (I will examine the various options for SPVs in a later post).

Having examined and analysed these basic structures the question which inevitably follows is how to choose between them, and that will be the subject of the next post.

Structuring Sourcing Projects (Part 1)

29/09/2010

Part 1

Common Structures

You might also like: